Tea ceremony as an art of seduction. Tea drinking in different countries. Chinese Tea Ceremony - Action Philosophy

The meaning of the gradual changes that took place in the Japanese culture of the 16th century is revealed with great completeness and conviction by the example of the cult of tea, with which the development of almost all types of art — architecture, painting, gardens, and applied arts was associated. It is especially significant that the ritual, denoted by the term “toa-no-yu”, translated into European languages as a tea ceremony, was not only a kind of synthesis of the arts, but one of the forms of secularization of culture, the transition from religious forms of artistic activity to secular. The tea cult is also interesting from the point of view of translating the "alien" into "its", assimilation and internal processing of ideas perceived from outside, which was the most important feature japanese culture throughout its history.

The so-called “School of sobbing jade” taught to mix powdered tea with a small amount of hot water in a paste in a pre-warmed tea cup. With the remaining water, tea was beaten with a broom made from chopped bamboo, until a solid foam crown formed on the surface. The winner of the tea contest was the one whose foam was as strong as possible, and which lasted a long time.

While in Japan in the past century, this method of tea growing became more popular and established itself as a ritual with fixed rules in Japanese culture, Chinese tea culture developed in subsequent dynasties in a completely different direction. In the course of this development, a variety of Chinese also developed. Based on the above definition, it can be called a tea ceremony, which is carried out with special efforts, efforts and care.

Determining the exact type of tea ceremony in the art system, using the categories of European art history, is not easy. She has no analogies in any artistic culture of the West or the East. The ordinary everyday procedure of drinking a tea drink was turned into a special canonized act that took place in time and took place in a specially organized environment. The “direction” of the ritual was built according to the laws of artistic convention, close to the theater, the architectural space was arranged with the help of plastic arts, but the goals of the ritual were not artistic, but religious and moral.

With the simplicity of the general scheme of the tea ceremony, it was a meeting of the host and one or several guests for a joint tea party - the focus was on the most careful design of all the details, down to the smallest, concerning the venue and its temporary organization.

One can understand why the tea ritual has taken such an important place, having been preserved for many centuries until modern times, only by examining and carefully analyzing it in the context of Japanese artistic culture and the characteristics of its development from the second half of the XV to the end of the XVI century.

As you know, the first tea drink began to be consumed in China in the era of the Tan (VII-IX century). Initially, infusion of tea leaves was used for medical purposes, but with the spread of Buddhism of the Chan sect (in Japanese - Zen), who considered long meditations as the main method of penetrating the truth, adherents of this sect began to drink tea as a stimulant. In 760, the Chinese poet Lu Yu wrote the Book of Tea (Cha Ching), where he outlined a system of rules for preparing a tea beverage by brewing boiling tea leaves. Tea in powder (as later for the tea ceremony) was first mentioned in the book of Chinese calligrapher of the XI century Jiang Xiang "Cha lu" (1053) 1. About drinking tea in Japan there is information in written sources of the 8th – 9th centuries, but only in the 12th century, during the period of increasing contacts between Japan and Sung China, drinking tea became relatively common. The founder of one of the schools of Zen Buddhism in Japan, Priest Eisai, returning from China in 1194, planted tea bushes and began to grow tea for religious ritual at the monastery. He also owns the first Japanese book about tea, Kissa Yojoki (1211), which also speaks about the health benefits of tea.

1 (See: Tanaka Sen "o. The Tea Ceremony. Tokyo, New York, San Francisco, 1974, p. 25.)

Strengthening the influence of Zen priests on the political and cultural life of Japan in the XIII-XIV centuries led to the fact that drinking tea spread beyond the borders of Zen monasteries, became a favorite pastime of samurai aristocracy, taking the form of a special entertainment contest on guessing a variety of tea grown in one or another terrain These tea tasting-tasting lasted from morning to evening with a large number of guests, and each received up to several dozen cups of tea. Gradually, the same game, but less magnificent in its surroundings, spread among the townspeople. Numerous references to it are found not only in the diaries of that time, but even in the famous chronicle "Taiheiki" (1375).

The tea master (tiadzin), who devoted himself to the tea cult, as a rule, was a well-educated man, a poet and an artist. It was a special type of medieval "intellectual" that appeared at the end of the XIV century at the Ashikaga shoguns court, inclined to protect the people of art. Living in a Zen monastery and being members of a community, the masters of tea could come from a wide variety of social strata, from high-born daimyo to urban craftsman. In the difficult conditions of social ferment, instability, the restructuring of the internal structure of Japanese society, they were able to maintain contacts with both the top of the society and the middle strata, sensitively catching the changes and reacting to them in their own way. At a time when the influence of orthodox forms of religion was declining, they consciously or intuitively contributed to its adaptation to new conditions.

The ancestor of the tea ceremony in its new form, which already had little to do with the court game of tea, is considered to be Murat Shuko, or Dzuko (1422-1502). He devoted his entire life to the art of the tea ceremony, seeing the deep spiritual foundations of this ritual, comparing it with Zen concepts of life and inner cultivation.

The success of his work, of course, was based on the fact that his subjective aspirations coincided with the general tendency of the development of Japanese culture in conditions of prolonged civil wars, countless disasters and devastation, the division of the whole country into separate hostile areas.

It is precisely because Murat Syuko’s activity expressed the social ideals of his time that the tea ceremony he created as a form of social intercourse quickly became widespread throughout the country and in almost all segments of the population. Being a citizen from among the townspeople (the son of a priest, he was raised in the family of a wealthy merchant of the city of Nara, and then a novice in a Zen temple), Syuko was associated with the emerging city class, which was first introduced to the culture, but did not have its own forms cultural activity and therefore adapted to their needs already existing. Living in a Buddhist monastery, Syuko was able to assimilate such established forms, traditional for feudal Japan, where monasteries were centers of education and culture. In their way of life and occupation, Zen novices were actually laymen: they could leave the monastery forever or for a while, could constantly communicate with citizens, and finally travel throughout the country. Zen monasteries conducted extensive economic and other practical activities, up to overseas trade, which was quite consistent with the basic tenets of the Zen doctrine 2.

2 (See: Sansom G. Japan. A short Cultural History. London 1976, pp. 356, 357.)

Zen-Buddhism, which received the status of a state ideology under the Ashikaga shoguns, was closely connected with the sphere of art, encouraging not only the study of Chinese classical poetry and painting, but also the own work of its adepts as a way to comprehend the ineffable words of truth. Such a combination of practicality and "life in the world" with a keen interest in art, characteristic of Zen, explains the tendency of secularization that began in the second half of the 15th century. A typical expression of this process was the gradual "shift of emphasis" in the functioning of certain types of art, especially architecture and painting, and their new connections with each other. But the most important thing was that the religious during this period not only gives way to the secular or becomes secular, but with this transformation takes the form of the aesthetic 3. Paradoxically, Zen Buddhism had a significant role in the secularization of art. In the study of Japanese artistic culture, it is important to emphasize some features of the teachings of this sect, since it was Zen that had the strongest, incomparable influence on the formation of the fundamental principles of Japanese aesthetic consciousness.

3 (See: Tanaka Ichimatsu. Japanese Ink Painting: Shubun to Sesshu. New York, Tokyo, 1974, p. 137.)

The characteristic quality of Zen, like the whole Mahayana Buddhism, was an appeal to all, not only the elect, but, unlike other sects, Zen preached the possibility of achieving satori - “enlightenment” or “enlightenment” - by any person in everyday life. , unremarkable everyday existence. Practicality and life activity constituted one of the characteristics of Zen doctrine. According to Zen, nirvana and sansara, spiritual and secular, are not separated, but merged into a single stream of being, denoted by the term Tao (way) taken from Taoism. The flow of being in Zen teaching became synonymous with the Buddha, and therefore not a metaphysical paradise, but everyday life was the object of the closest attention. Any ordinary event or action, in the opinion of Zen adepts, can trigger an “enlightenment”, becoming a new world view, a new sense of life. Hence, the rejection of esotericism and sacred texts, as well as of a specific religious ritual (its absence made it possible to turn into a ritual of any action, including drinking tea). Not only monks and priests could be followers of Zen, but any person, whatever he did and no matter how he lived.

In the preceding historical period, the Zen sermon, mainly aimed at representatives of the military class and bringing up fighting spirit, contempt for death, endurance and fearlessness, now, with the increasing social significance of the townspeople - merchants and artisans, turned out to be turned in their direction. Such an appeal to new social strata required different forms, orientation to other tastes and needs. If before Zen ethics singled out the ideas of vassal devotion and sacrifice, now it turned into a "philosophy of life", a practical activity, especially close in attitude to the emerging urban class. By the utopian "removal of oppositions" characteristic of the very structure of his thinking 4, Zen compensated for the insolvability of the real contradictions of the social life of Japan at that time. In the field of artistic culture, with its general tendency of secularization, Zen's characteristic shift of attention from mystical, religious contemplation to aesthetic experience as its analogue turned out to be extremely effective. This was connected with the doctrine of the direct, intuitive, non-verbal understanding of truth through a work of art. It was precisely in the Zen teaching that it could become a source of truth, and the ecstatic experience of beauty was an instant contact with the Absolute. Since the very fact of the knowledge of truth had an ethical meaning (it was a "virtue" if to use the analogy with Christianity), the increased attention to art and to the creative act itself was highly characteristic of Zen (it was not for nothing that Zen priests were the creators of the majority of landscape gardening ensembles , scrolls of monochrome painting, outstanding examples of ceramics, they were also masters of tea).

4 (See: I. Abaev. Some structural features of the Ch'an text and Chan Buddhism as a mediative system. - In the book: The Eighth Scientific Conference "Society and State in China", vol. 1. M., 1977, p. 103-116.)

The Zen concept of "insight" is the most important moment not only of the Zen theory of knowledge itself. It involves a special type of perception, including the perception of a work of art. And accordingly, the structure of the artistic image in Zen art (the very type of plastic language, composition, etc.) is designed specifically for this type of perception. Not a gradual advancement from ignorance to knowledge, in other words, a consistent, linear perception, but an instant grasp of the essence, the whole fullness of meaning. This is possible only in the case when the world is initially represented as integrity, and not as multiplicity, while the person himself is an organic part of this integrity, not isolated from it and therefore not opposed to it as a subject to an object.

The paradox in the structure of Zen thinking sometimes meant a negative attitude to everything generally accepted. "When someone asks you a question, answer it negatively if it contains any statement, and vice versa, affirmatively, if it contains denial ..." - these words belong to the sixth Zen patriarch who lived in China in VII century and outlined the basics of zen doctrine 5. In accordance with such an attitude of consciousness, the most base and despised could become valuable, leading to blasphemous statements from the standpoint of orthodox Buddhism (for example, Buddha is a piece of dried shit; nirvana is a pole for tying donkeys, etc.); beautiful, on the contrary, could turn out to be what by previous standards was generally beyond the aesthetic. In Japan, the end of the XV-XVI centuries, it was the whole range of household items of the poorest segments of the population - the peasantry, urban artisans, small traders. A shabby thatched hut, utensils made of clay, wood, and bamboo were opposed to the criteria of beauty embodied in the architecture of the palace, the luxury of its furnishings.

5 (See: I. Abaev. Some Structural Features of the Ch'an Text .. p. 109.)

It is this movement of high and low in the hierarchy of aesthetic values that was carried out by the masters of tea and embodied in the ritual of tyu-no-yu. Claiming new criteria for beauty, the tea cult, at the same time, used the already established system of types and genres of art, only by choosing for itself the right and appropriate one. In the tea ceremony, all this was combined into a new unity and received new functions.

Murata Syuko reinterpreted the already existing forms of tea ritual - monastic tea drinking during meditations and court tea competitions from the point of view of the Zen world perception and Zen aesthetic ideas. Having given the tea competition at the Ashikaga Yoshimas court the Zen meaning of separating from the world of vanity for immersion into silence and inner cleansing, Syuko first began to create that form of ritual that received its full expression from his followers in the 16th century.

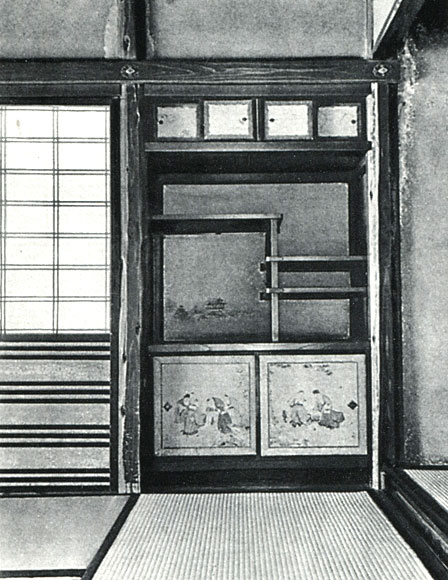

In an era of unrest and incessant civil wars, tea ceremonies at Yoshimas' court, with their refined luxury, were an escape from the harsh reality and a “game” of simplification. Next to the Silver Pavilion in the so-called Togudo, there was a small room (less than three square meters), which Suko used for tea ceremonies that became more intimate and not crowded. The walls of the room were covered with light yellow paper; under the scroll of calligraphy there was a shelf with tea utensils set apart to admire. In the floor of the room was a hearth. It was the first room specially equipped for the tea ceremony, which became the prototype for all subsequent ones.

For the first time, Syuko himself prepared tea for guests, and also used, along with Chinese utensils, products made in Japan that were most carefully and carefully made. Such an aesthetic compromise was not accidental and had its reasons related to the underlying processes that took place in the depths of the gradually changing structure of Japanese society, which later led to the formation of purely national ideals of beauty.

Comparing the two periods of Japanese culture, defined as Chitaim (Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu's reign - late XIV and early XV century) and Higashiyama (Ashikaga Yoshimas's reign - second half of the XV century), Professor T. Hayasiya sees the basis for their significant difference in that For the first time, the Higashiyama culture actively involved representatives of the urban merchant elite, who had no impact on the Chinese culture. 6 Wealthy townspeople maintained close contacts with the country's political leaders, providing them with constant financial support and receiving for this the right to overseas trade with China. The main articles imported from China along with copper coins and textiles were paintings and scrolls of calligraphy, porcelain and ceramics. Passing through the hands of merchants as valuable and prestigious things, they began to receive in their eyes also cultural value. However, being in constant touch with works of art as a commodity that gave them enormous profits, the townspeople could not fail to bring into their perception the consciousness of their usefulness and practical benefits. So gradually, a symbiosis of the concepts “beautiful” and “useful” arose, which later, having taken a completely different form, had a significant impact on the entire aesthetic program of the tea cult.

6 (See: Hayashiya Tatsusaburo. Kyoto in the Muromachi Age. - In: Japan in the Muromachi Age. Ed. J. W. Hall and Toyoda Takeshi. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1977, p. 25)

Awareness of what is useful as beautiful signified the inclusion of the thing in the sphere of emotional perception, and through it in the wider spiritual sphere. The real meaning of the thing, its practical function was transformed into an ideal value or even received a multitude of meanings. Comparison, and then combining the concepts of "beauty" and "benefit", which arose in the environment of the urban class that had been formed and first joined the cultural sphere, had extremely important ideological consequences, which gradually led to the desacralization of the beautiful, its becoming worldliness, which was especially evident in the tea ceremony , the further evolution of which was influenced by impulses emanating from the environment of citizens.

This evolution is associated with the name of Takeno Zyoo, or Shyo (1502-1555), the son of a wealthy tanner from the city of Sakai, a flourishing port and commercial center near Osaka. In 1525, Joo came to Kyoto to learn versification, and at the same time began to take tea ceremony lessons from Shuko. More familiar with the life of the urban class, who took it more organically than Syuko, his worldviews, Joo and in tea cult To the ideas that expressed the most democratic sides of the Zen doctrine: equally open to “enlightenment” through contact with the beautiful, simplicity and unpretentiousness of the situation and utensils, etc. Syuko, being at the shogun's court, could declare these ideas more, what to embody, and joo tried to find them specific forms of expression. In the procedure developed by Syuko, Zouo introduced elements of the so-called tea meetings, widespread among the townspeople. It was also a type of social intercourse, but, unlike the court ritual, on a more domestic and pragmatic level and with other tasks. A friendly conversation over a cup of tea was also a business meeting, and with representatives of the upper classes. Mastering the manners and rules of "good taste" for such meetings became the germ of tea ceremony etiquette.

But the most important idea enshrined in the tea ceremony of joo was the idea of equality. Constant business contacts of the samurai elite with the urban trading elite were expressed not only in the desire of the latter to imitate the lifestyle of the upper class, including the collection of works of art and expensive tea utensils. This was the emergence of a new class of self-consciousness, which was growing economically, but completely devoid of political rights and was trying to establish itself at least at the cultural and everyday level.

The stage of formalizing the tea ceremony as a complete independent ritual with its own aesthetic program is associated with the name of the highly revered Japanese master Senno No Rikyu (1521-1591), whose life and activities reflected the complexity and uniqueness of the cultural situation in Japan in the 16th century.

Rikyu was the grandson of Senami, one of the advisers (dobosyu) at the court of Ashikaga Yoshimas, and the son of the wealthy merchant Sakai. In 1540, he became a student of the returning Sakai Joo. He brought to the highest perfection not only the ideas of his direct teacher, but also the ideas of Syuko, connecting them also with some features of the refined style of court tea competitions.

The erection of a tea house by the master jo (tashitsu) was an important act of establishing the ritual as an independent action, leading to the establishment of rules of behavior and the organization of the environment. Since tea houses were built in Zen monasteries and in cities, close to the main apartment building, usually surrounded by at least a small garden, the idea of a special tea garden (pulln), whose design was subject to the rules of ritual, gradually emerged. Rikyu belonged to the basic principles of creating such a garden. He developed the design of the house, ranging from orientation to the countries of the world and the associated illumination and ending with the smallest features of the organization of the inner space.

Although the role of Rikyu in the formation of the principles of the tea ceremony was predominant, with the change of the social situation in the country in the last decade of the XVI century and especially in the beginning of the XVII century, other modifications of the ritual appeared. Sublime ideas and the harsh seriousness, which animated Rikyu's creative activity, began to contradict the general tendency of Japanese culture. It is not by chance that Saint-No Rikyu himself and his famous student Furuta Oribe (1544-1615) were forced to commit ritual suicide (seppuku).

Already, Oribe had a slight shift of emphasis in the general mood and entourage of the tea ceremony. He was the first to consciously introduce the concept of the game into the world of the tea cult. 7 The hue of entertainment (once peculiar to court tea competitions) made the ceremony more accessible to ordinary people, mainly city dwellers, with their unpretentious inquiries and burdens to enjoy life, and not to deep thinking. But from his great teacher, Oribe took a programmatically creative attitude to tradition and further emphasized the role of the tea master as an artist, as a person endowed with great creative power and imagination. He owns a significant number of ceramics, so personally defined and having no analogies, that the very concept of "oribe style" has become nominal: they are characterized by rectangular shapes with accentuated asymmetrical decor or glazed with contrasting colors.

7 (See: Hayashiya Tatsusaburo, Nakamura Masao, Hayashiya Seizo. Japanese Arts and the Tea Ceremony. New York, Tokyo, 1974, p. 59.)

After Sen-no Riku, the category of personal artistic taste (the so-called bitch) is established in the tea cult, and the evolution of the ritual itself is divided into two directions, one of which was a continuation of his style (his sons and grandchildren who founded the Urasenke and Omotekenke schools) the second, which received the name "daimyo style", turned into a refined and emphasized refined pastime for the elite of society. The founder of this trend is considered to be the famous master of tea and the artist of the Kobori Aeneas gardens (1579-1647).

In order to understand and evaluate as a creative act equal to the creation of a painting or a garden, what was done by tea masters of the end of the 15th and 16th centuries, it is necessary to more accurately imagine the procedure of the tea ceremony itself.

This etiquette, as well as the whole environment, was created gradually. Each tea master, in accordance with his own ideas, as well as the composition of the invitees and specific features of the moment, right up to the weather, acted as an improviser, creating every time a different, unique action, using the main established clichés. The impossibility of absolute repetition created the attractiveness and meaning of each tea ceremony, which with a high degree of conditionality can be likened to a theatrical performance that is born again and again every evening on stage, although it is based on the same piece.

The development of the etiquette of the tea action, which took place simultaneously with the formation of its spiritual foundations and the organization of the environment, was the “japonization” of the custom that came from the continent, its adaptation to specific cultural and everyday conditions.

His first beginnings were already in the ceremonies, which were conducted by the court councilors (before the tribe), who set up the utensils in a certain order and prepared tea for the owner and his guests. Suko, who was the first to make tea for the guests himself and act as a master, sought first to give spiritual meaning to all actions and called for concentration on every movement and gesture, just as Zen teachers were forced to focus on the inner state, mentally moving back. from the outside world and plunging into a state of meditation, when the consciousness is turned off, as it were, but the sphere of the subconscious is activated 8. Developed by his followers, Zзоo and Sen-no-Riky, the whole ritual was built on the basis of a certain system of rules for both the host and guests, whose behavior should not go beyond these rules, otherwise the whole action, its carefully thought-out unity, would have broken up 9 . The rules varied depending on the time of the day at which the ceremony was held (in the evening, at noon, at dawn, etc.), and especially on the season, as the underlining of signs of a certain season and associated feelings was traditional for all Japanese artistic culture.

8 (Although the Zen doctrine proclaimed a negative attitude towards canonical texts and rituals, in fact, the founders of the sect Eisai and Dogen developed a charter for the practical life of the Zen community, regulating everything down to the smallest detail, including eating, washing, dressing, etc. (see: Collcutt M. Five Mountains., The Rinzai Zen Monastic Institution in Medieval Japan. Cambridge (Mass.) And London, 1981, pp. 147-148). At the same time, they did not simply explain how everything is done and for what, but they connected it with Zen doctrines, highlighting as the most important need to focus on all the most elementary functions. Thus, the daily life of the members of the community consisted not only of many hours of contemplation, but also of work, and each action became a ritual in which the basics of learning were comprehended in the same way as when listening to sermons or in moments of self-deepening while contemplating. Ritualization as a method of transforming the everyday into the sacred, low into the high and served as a model for the activities of the masters of tea.)

9 (Wed the idea of a "game" as an "order" in the book: Huizinga J. Homo Ludens. Haarlem, 1938, p. ten.)

The host, the tea master, invited one or several guests (but not more than five) to the ceremony, setting a specific time. The guests gathered about half an hour before the start and waited on a special bench for waiting. The ceremony began with the guests entering through the gate to tea garden, silently following through it, washing the hands and rinsing the mouth at the vessel with water (in winter, the owner prepared for this warm water, and in the dark endured the lamp). Then, one by one, the guests entered the tea house, leaving their shoes on a flat stone at the entrance, and the last guest shoved the door with a light knock, signaling to the owner that everyone had already arrived. At this time a host appeared, who greeted the guests with a bow at the threshold of the back room (mizuya).

The making of fire in the hearth could occur at guests or before their arrival. Guests seated on tatami facing the owner. The main guest is at the place of honor, near the niche where the painting hangs or there is a vase with a flower and a censer with incense. The owner began gradually, in strict order to make utensils. At first - a large ceramic vessel with a lid clear water. Then - a cup, a whisk and a spoon, then a teapot and at the end - a container for used water and a bamboo ladle. There is a certain order of removal of all items from the tea room to the utility after the ceremony 10. The most important moment of the ceremony was the preparation of utensils - its purification, of course, symbolic, with the help of fucus - a folded piece of silk fabric. When the water in the iron pot suspended above the hearth began to boil, the owner scooped water with a long-handled wooden ladle and warmed it with a cup and a special bamboo whisk for beating powdered green tea. Then the cup was carefully wiped with a linen napkin. With a long bamboo spoon, the owner took out tea powder from a teapot and, filling it with water, whipped it into a foam with a broom. This was the most crucial moment, as the quality of tea depended on the ratio of water and tea, on the speed of the whisk and the duration of churning, not to mention the temperature (in the hot season, for example, just before preparing the tea, add one to the kettle). cold water bucket).

10 (See: Castile R. The Way of Tea. New York, Tokyo, 1971, pp. 274-278.)

Both the choice and the order of placing things on the mat in front of the owner depend on which of the two main types of ceremony takes place - the so-called ko-ty (thick tea) or usu-ty (liquid tea). Sometimes they form two phases of the same ceremony, with a break and guests in the garden to relax.

Thick tea is prepared in a large ceramic cup, and each of those present takes a sip from it, wipes the edge of the cup and passes it to the next guest. Liquid tea is prepared in a slightly smaller cup personally for each guest, after which the cup is washed, wiped and the procedure is repeated. In the preparation of liquid tea seventeen different phases are distinguished. 11 After the tea is drunk, the guest carefully examines the cup, which stands on his left palm. He turns her fingers right hand (also in the established order) and enjoys not only its shape, color, but also its texture, the beauty of its inner surface, and then, turning it over, its bottom. The cup should not be too thin so as not to burn the hands, but it should not be too heavy so as not to tire the guest. The thickness of the walls of the cup varies depending on the warm or cold season. Associated with this is its shape - more open or closed, deep or shallow.

11 (Ibid., P. 277.)

In the coy-toa ceremony, a ceramic tea-pot (cha-ire) is used in the form of a small bottle with an ivory cap. Green tea powder is poured into it (it should be fully used at one ceremony). For usutya necessarily take lacquer tea (natsume), and tea powder in it may remain after the ceremony. Tya-ire put on a lacquer tray, and natsume - directly on the mat.

A bamboo spoon for taking out a powder from a teapot is a matter of special pride of every tea master. It is about her conversation begins after tea. Polished by hands from long-term use, simple and unpretentious, such a spoon most fully embodied the "spirit of tea", the most appreciated bloom of antiquity, patina, which is fragile and seemingly short-lived on things. The same patina of antiquity was valued in ceramic things and in an iron pot, where water was boiling. Only a linen napkin and a bamboo dipper were emphasized. New could be bamboo whisk for churning tea.

Leisurely, calm, measured movements of the master of tea not only, like dancing, were of special interest to the guests, but they also created a general atmosphere of peace, inner concentration, detachment from everything else that is not relevant to the act. When the tea was over and the owner closed the lid of the vessel with cold water, it was time to admire the utensils - a bamboo tea spoon, a caddy, a cup. After that, a conversation could arise about the merits of the utensils and its choice by the host for the occasion. But the conversation was not required. The inner contact of the participants was considered more important, "silent conversation" and insight into the innermost essence of objects, the intuitive comprehension of their beauty. Yes, and the entire external drawing of the action was considered secondary in the ceremony. Behind him was a complex subtext, each time different depending on the specific conditions. He was the main spring of the ritual, everything was subordinated to his understanding, and all the elements of the ceremony became the means of its formation and identification for the participants.

Thus, the whole action consisted of a consistent chain of “game” situations, which acquired, by virtue of their underlined significance, additional symbolic meaning.

Each participant performed a number of canonized actions, but the ultimate goal of the ceremony, as if encrypted in them, was to throw off the shackles of everyday life consciousness, free it from the vanity of real life, a kind of “filtering”, purification for perception and experience of beauty. The conditionality of the ritual situation consisted in the fact that the person in the tea ceremony was as if deprived of his various properties and qualities, their unique individual combinations. They temporarily "rejected", remained on the other side of the gates of the tea garden, and one quality was especially emphasized - receptivity to the beautiful, readiness for its emotional and intuitive comprehension. All participants experienced beauty in their own way, although the canonical construction of the action was focused not so much on different reactions of people as on the identity of the very ability to comprehend beauty, sublimation of spirituality through aesthetic emotion. But the possibility of this arose only by virtue of the very construction of the ritual, its organization according to the laws of a special convention - the laws of the artistic work. The collective creative act of tea masters of the end of the XV - beginning of the XVI century and consisted in the awareness of these laws and the creation on their basis of the individual components of complete integrity.

The early form of the tea house ideologically and stylistically went back to residential architecture, both in design and in the way space was organized. But at the same time, Tysytsu was not intended for housing, and its internal space during the ceremony functioned as sacral, suggesting actions that had symbolic significance and differed from ordinary ones. The idea of the house-temple was not new for Japan - it goes back to the ancient Shinto concepts. But the tea house, rather, can be characterized in the negative definitions characteristic of Zen Buddhism: “non-house”, “non-temple”. He was also supposed to resemble a hermit asylum or a fishing house built from the simplest and most common materials - wood, bamboo, straw, and clay. The first tea houses were built on the territory of Zen monasteries, were surrounded by a garden, hidden from the eyes behind a fence, which contributed to the feeling of their privacy. At the beginning of the XVI century, with the wide spread of the tea cult, tea houses began to be built directly in the cities, which were already quite closely and densely built up. Even rich citizens could take a very small piece of land under the tea house, which reinforced the tendency towards simplification and compactness of its design. Thus, the most common type of “shan’s style” (reed hut), the most widespread throughout the whole century, gradually became more and more different in its details from the main type of residential building of that time. Thus, the very strict restrictions and minimal funds that came into the possession of tea masters that arose due to specific historical conditions contributed to the creation of a very special environment for the tea ceremony.

In the early form, as in a residential building, there was a veranda, where guests gathered before the start of the ritual and where they rested during the break. The tendency to more compact structures led to the abandonment of the veranda, which in turn caused significant changes in the interior and especially in the garden, where a bench for waiting appeared, and before the entrance to the house there was a special hanging shelf where they left swords. at the entrance to the veranda).

Already in the times of Takeno Jo, they began to make a lower entrance to the tea room, and Sen-no Rikyu made a square opening about 60 cm in height and width. Scale reduction of the entrance was associated with a general decrease in taxes (Rikyu built a measure less than four square meters in size), but this was also its symbolic meaning of equality of all in the tea ceremony: any person, regardless of class, rank and rank, had to bend down to step over the threshold of the tea room, or, as they said, "leave the sword beyond the threshold."

52. The scheme of the garden and the pavilion for the tea ceremony. From the book "The Art of Tea". 1771

In its construction, the tea house proceeded from Japan’s traditional frame building system, as it was traditionally based on the main building material - wood. Under special seismic conditions, in hot and humid climates, the most rational building system gradually developed from antiquity: on the basis of a light and elastic wooden frame, with walls that did not have support functions, raised high above the ground floor level and a sloping roof with a wide overhang. This basic scheme has varied and changed over the centuries depending on the functional features of religious and residential architecture, the social and spiritual development of society. This scheme is visible in the construction of the palace of the X century, and the Buddhist temple of the XIV century, and the residential building of the XVII century, which can be judged by some of the preserved monuments, reconstructions and images in paintings. The design of the tea house, which appeared at the end of the XV and the beginning of the XVI century, was no exception. In the interior, two basic elements characteristic of the living quarters of the military class remained: the niche (tokonoma) and the floor covered with straw mats (tatami) as the main "vital surface". Standard sizes of mats (approximately 190 X 95 cm) made it possible not only to determine the size of the room, but also all proportional relations in the interior. The size of the tea house Zо was four and a half tatami, most common throughout the XVI century. The only one attributed to Rikyu Tashitsu, preserved to our time, is Tai-an in Mekki-an monastery in Kyoto - it is only two tatami-sized. In the square recess of the floor (half the size of tatami) was located the hearth used for ceremonies in the winter time.

The height of the ceiling in the tea room was approximately the length of the tatami, but was different in different parts of the room: the lowest ceiling was above the place where the owner sat. Made from natural unpainted materials, as, indeed, all other elements of the roof, the ceiling could vary in different parts - from simple boards to patterned woven panels of bamboo and reeds. Special attention was paid to the ceiling in those places where windows were installed in the roof or the upper part of the wall, such as in Jan.

In the very first tea houses there were no windows at all, and the light penetrated only through the entrance for guests. Since the time of Rikyu, great importance was attached to the arrangement of windows, their placement, shape and size. Usually small in size, they are located irregularly and at different levels from the floor, being used by the masters of tea to accurately “meter” natural light and its focus on the desired area of the interior. Since the interior was designed for the half-figure of a person sitting on a mat, the most important was the illumination of the space above the floor. The floor-level windows are located in the Teygoku-ken tea pavilion in Daitokuji and in a number of others. The windows did not have frames and were closed with small sliding doors covered with paper. From the outside, in order to reduce the light penetrating inside, they were supplied with a retractable bamboo grate. The location and level of the windows were calculated so as to illuminate first of all the place in front of the owner, where the tea utensils were placed, as well as the hearth and tokonoma. Some tea houses had skylights that gave the upper light and were usually used during ceremonies held at night or at dawn. Both tatami and tea house windows, depending on their location, are designated by special terms 12.

12 (Ibid., Pp. 175-176.)

The walls of most tea houses, preserved to our time from the XVI-XVII centuries, as well as reconstructed according to old drawings, are earthenware with a diverse texture resulting from the addition of grass, straw, small gravel to clay. The surface of the wall with its natural color is often preserved both outside and inside, although in some areas the lower part of the walls in the interior is covered with paper (in Joan these are pages of old calendars), and the outer one is plastered and whitened. The clay walls are framed with corner posts and structural beams, often made from specially selected logs with a beautiful texture. In addition to window openings, Tysytsu has two entrances - one for guests (nijiri-guchi) and the other for the host. Next to the higher entrance, for the owner, there is a utility room - mizuya, where all the tea utensils are placed on the shelves.

In many tea houses (Hasso-an, Teigyoku-ken and others) that part of the room, from which the owner appears, is separated from the main by a narrow, not reaching the floor wall, located between one of the uprights supporting the roof and Basirah), whose origin goes back to the most ancient sacral structures.

Naka-basira does not determine the geometric center of the room, and practically has no support functions. Its role is primarily symbolic and aesthetic. Most often, it is made from a natural, sometimes even slightly curved and bark-covered tree trunk. In the interior of the tea room with a clear linearity of all the outlines of the naka-basira was perceived as a free plastic volume, like a sculpture, organizing space around itself. Naka-basira evoked associations with the unsophisticated simplicity of nature, devoid of symmetry and geometric regularity of forms, necessary in aesthetics of the tea ceremony, emphasized the idea of the unity of the house and nature, the absence of opposition to the man-made structure and the non-human world. According to tea masters, naka-basira was also the personification of the idea of the “imperfect” as an expression of true beauty. 13

13 (Laozzi owns the words: "Great perfection is like imperfect." Quoted by: Ancient Chinese Philosophy, vol. 1, p. 128)

The interior of the tea house had two centers. One - on a vertical surface, a tokonoma, and the second - on a horizontal one, this is a center in the floor.

Tokonoma, as a rule, was located directly opposite the entrance for guests and was their first and most important impression, as the flower in it in a vase or scroll became its glad key sign of the ceremony, defined the “field of ideas” and associations offered by the host.

The details of the tea house, as well as all the details of the garden and tea utensils, must be conceived not only to clarify the individual stages of the ritual, but in this case to understand the process of gradual comparison of a completely specific architectural space, the construction of individual parts with religious -philosophical concepts that were concretized in this way, “germinated” into the sphere of the person’s direct life experience and were themselves modified, turning into eptsii aesthetic.

57. Diagram of the device bench for waiting and a vessel for washing hands in the tea garden. From the book "The Art of Tea", 1771

For example, the first tea masters associated the small size of the tea house with the Buddhist idea of the relativity of space for a person seeking to overcome the limitations of his own "I", to inner freedom and looseness. The space was perceived not only as a room for ritual, but was itself an expression of spirituality: the tea room is a place where a person is freed from the constant enslavement of material things, everyday desires, can turn to simplicity and truth.

Comparison of abstract and difficult to understandable untrained consciousness of philosophical ideas with the concreteness of the objective everyday world was the essence of the creativity of tea masters, reflecting the processes that took place in the Japanese culture of that time. Therefore, the tea cult itself can be interpreted at the level of Zen concepts and the transition of the religious to the aesthetic, but also at the level of social and everyday life, as the addition of new forms of social behavior and communication.

Thus, already at the first tea masters the rite as a whole and all its elements received an ambiguous, metaphorical meaning. The world of everyday objects and simple materials was filled with new spirituality and, in this capacity, opened up to very wide sections of society, acquiring features of national ideals.

Murata Syuko formulated the so-called four principles of the tea ceremony: harmony, reverence, purity, silence. The whole ceremony as a whole — its meaning, spirit, and pathos — and also every component of it, down to the smallest details, should have become their embodiment. Each of the four principles of Syuko could be interpreted both in the abstract-philosophical sense and in the concrete-practical one.

The first principle implied the harmony of Heaven and Earth, the orderliness of the universe, as well as the natural harmony of man with nature. Man’s naturalness, liberation from the conventionality of consciousness and being, enjoying the beauty of nature until merging with it - all these are internal, hidden goals of the “tea path” that received external expression in harmony and simplicity of the tea room, the relaxed, natural beauty of all materials - wooden details structures, mud walls, iron pot, bamboo whisk. Harmony also implies the absence of artificiality and stiffness in the movements of the master of tea, the general atmosphere of ease. It includes a complex balance in the composition of the picturesque scroll, the painting of the cup, when external asymmetry and apparent coincidence turn into internal balance and rhythmic orderliness.

The reverence was associated not only with the Confucian idea of the relationship between the higher and the lower, the older and the younger. The tea ceremony at the time of Joo and Rikyu, asserting the equality of all participants, implied their deep respect for each other, regardless of class status, which in itself was an unprecedented act in the conditions of the feudal social hierarchy. In the tea cult, a sense of reverence had to be experienced in relation to the world of nature, personified by a single flower in a vase, a landscape roll in a tokonoma, few plants and garden stones, and finally, the general spirit of "miraculous" naturalness characteristic of tsyatsu and all the objects used in ritual, without division into important and unimportant. The concept of reverence, respect included a shade of mercy, compassion, as well as the idea of a person’s limitations - physical and spiritual, intellectual and moral - resulting in his constant need for contact with infinity.

The principle of purity, so important in Buddhism and dominant in the national Japanese religion of Shinto, in the tea ceremony received a sense of purification from worldly dirt and fuss, internal purification through contact with the beautiful, leading to the comprehension of truth. The ultimate cleanliness, which is inherent to the garden, the house and each piece of utensils, was specially emphasized by ritual cleansing - wiping a cup, teapot, spoon, and ritual washing of hands and rinsing the mouth with guests before entering the tea room.

No less important was the fourth principle put forward by Syuko, the principle of silence, peace. He proceeded from the Buddhist concept, defined in Sanskrit by the term vivikta-dharma (enlightened loneliness). In Zen art these are qualities that do not cause affectation, excitement, do not interfere with inner calm and concentration. The whole atmosphere of the tea room, with its shading, muffled color combinations, slowness and soft smoothness of movements, was conducive to self-absorption, “listening” to yourself and to nature, which was a necessary condition for the participants in the ceremony to speak silently without words. .

The first two principles — harmony and reverence — had mainly a social-ethical meaning, the third, purity, physical and psychological, and the most important, fourth, silence, spiritual and metaphysical 14. Ascending to the Buddhist notions of nirvana as blissful peace, in the tea cult it is associated with the aesthetic categories of wabi and sabi, which are close in meaning to each other, but have important differences.

14 (See: Suzuki D.T. Zen and Japanese Culture. Princeton, 1971, p. 283, 304.)

Like other categories of Japanese medieval aesthetics, they are difficult to translate, even descriptive. Their meaning can best be expressed metaphorically-figuratively - in verses, in painting, in things, and also in the qualities of the environment as a whole.

The embodiment of the concept of wabi is a short poem by Saint-No Riku:

"I look around - no leaves, no flowers. On the seashore - a lonely hut In the glow of an autumn evening."

Perhaps even more convincing is the poem of the famous poet of the seventeenth century Basho:

"On a bare branch the Crow sits alone. Autumn evening."

(Translated by V. Markova).

"Sabi creates an atmosphere of loneliness, but it is not the loneliness of a person who has lost his beloved creature. It is the loneliness of rain falling at night on a tree with broad leaves, or the loneliness of a cicada rattling on bare whitish stones ... In an impersonal atmosphere of solitude is the essence of saby. Sabi is close The concept of wabi is in Rikyu and differs from wabi in that it embodies rather a dismissal than an introduction to simple human feelings ”15.

15 (Ueda Makoto. Literary and Art Theories in Japan. Cleveland 1967, p. 153. For more information about the category of saby in the aesthetics of Basho, see: TI Breslavets. Poetry of Matsuo Basho. M., 1981, p. 35-45.)

The combination of the concepts of wabi and sabi means the beauty of dim, mundane and at the same time sublime, not immediately revealed, but in a hint and details. It is also invisible beauty, the beauty of poverty, unsophisticated simplicity, living in a world of silence and silence. In the tea cult, the concepts of wabi and sabi became the personification of a completely specific style, the expression of certain techniques and artistic means as an integral system.

The style of the tea ceremony, which emphasizes in the first place simplicity and unpretentiousness, refinement of the "imperfect", is defined as the "wabi style". According to legend, the most complete "wabi style" was embodied by Saint-no-Rikyu and his followers in thee-no-yu.

In accordance with the four principles of Syuko and the general Zen concepts, Rikyu thought over to the smallest details the design of the tea house, the interior design and the choice of utensils. He defined the “direction” of the whole action in the space of the garden and at home and in time of its rhythmic flow with accelerations, decelerations and pauses: the theatrical conventionality of any movement and action received, in his interpretation, a “secondary” meaning, an additional deep meaning. This was exactly the case, although with the paradox of Rikyu characteristic of Zen thinking and his followers, they argued that spontaneously natural behavior, simplicity and ease of all actions were necessary. The Zen idea of non-doing as a lack of deliberate effort or desire for something is embodied in the words of Rikyu, spoken to him in response to the question of what is the meaning of the tea ceremony: "Just warm the water, make tea and drink it."

But at the same time, in the very specificity of the ritual, all the stages of the tyu-no-yu and all the details of the situation received from Saint-No Rikyu an exact awareness of their function and meaning. The integrity of the ceremony was based on the canonical fixation of the main course of action, as well as on the unity of the artistic principles of building the garden, the house, the composition of the painting, the decor of the ceramic cup. Harmony and tranquility of the general impression were combined with the hidden “charge” within each component of the ritual, which contributed to activating the emotional sphere of the people participating in it.

Tea masters paid close attention to the organization of the space around the tea house, which resulted in the emergence of a special tea garden (Tanya), which became widespread from the end of the 16th century.

If the basis for the emergence of a specific form of the tea house was the previous architectural experience embodied in the Buddhist and Shinto temple, the form of the tea garden developed on the basis of a long tradition of garden art.

Before the type of the actual tea garden was formed, in Japan for many centuries the art of gardens developed as an independent branch of creativity. Developed by Zen adepts, the canons of building a temple garden served as the basis for organizing the natural environment of the tea house. Masters of tea used the same means of expression, only adapting them to new conditions and new tasks.

64. A cup for the tea ceremony "Asahina". Ceramics seto. Late XVI - early 17th century

Constructed, as a rule, on a small plot of land between the main buildings of the monastery (and later - in conditions of close urban development), at first tea houses had only a narrow approach in the form of a walkway (roji), which in exact translation means "land moistened with dew." Subsequently, this term began to denote a more extensive garden with a number of specific details. By the end of the 16th century, the tea garden received a more expanded form: it began to divide by a low hedge with a gate into two parts - the outer and the inner.

65. The downside of the cup "Asahina"

The passage through the garden was the first step of detachment from the world of everyday life, a switch of consciousness for the fullness of aesthetic experience. As conceived by the masters of tea, the garden became the boundary of two worlds with different laws, rules, and norms. He physically and psychologically prepared man for the perception of art and, more generally, beauty. It was the garden that was the first act of the "performance" of tya-no-yu, the entry into the sphere of values other than reality.

66. A cup for the Miyoshi tea ceremony. Korea. XVI. Mitsui Collection, Tokyo

The process of value reorientation, which to a certain extent was the goal of the whole ceremony, began from the very first steps in the garden, washing the hands from a stone vessel with water. And precisely because the garden was very small, and the passage through it was so short, each, the smallest detail was carefully thought out and trimmed. During this short time, the garden gave a variety of impressions, and not random and chaotic, but foreseen in advance. Together, they were supposed to contribute to the state of peace and tranquility, concentrated detachment, which was required to participate in the ritual. Thus, the entrance to the garden was the entry into the "game space", the conditionality of which was originally set and resisted the "unconditionality" of the real, left on the other side of the gate. Passing through the garden was already the beginning of a “game”, a special theatrical, conditional behavior.

67. A cup for the tea ceremony "Inaba Tammoku". China. XIIIc. Seikado, Tokyo

Following the passage through the garden, the important moment of the ritual was the contemplation of the tokonoma. Internal emotional tension intensified due to a whole range of new sensations: a small closed space with calm cleanliness of lines, soft semi-darkness and consistency with the location and light of a tokon, the composition in which, as it were, opened for the first time the inner impetus of the ritual offered to the guests associations.

The tea room was deprived of visual connections with the outside world, and the picture in the niche, the flower in the vase became an echo of nature, hidden from view. As a result, it had a stronger emotional effect than direct comparison of one with another. There is a famous story about how military dictator Toyotomi Hideyoshi heard about unusually beautiful bindweed grown in the garden of Saint-no Rikyu, and wanted to admire them. Entering the garden, he frowned harshly at the sight of all the flowers being torn off. But inside the tea house, in a niche, there was an old bronze vase with one single, the best flower, as if embodying with the greatest fullness the unique beauty of the bindweed.

The composition in the tokonoma for guests who have just entered the tea room, personified the natural world in such its most concise and concentrated expression as a bouquet or a scroll of painting.

Tyabana - flowers for the tea ceremony, figuratively speaking, a bouquet - was chosen in accordance with the general rules of the ritual, but its special purpose was to emphasize the season, hint at the features of this unique situation. Sen-no Rikyu is considered the author of the main rule of the Teaban: “Put flowers as you found them in the field,” that is, the main task in arranging flowers for the tea ceremony was the most natural, without striving to express something besides their own beauty, which was typical for ikebana - special art of flower arrangement 16. In Tyaban, they do not use flowers with a strong odor that would prevent them from enjoying the aroma of the censer. Preference is field and forest flowers, more consistent with the ideals of the tea cult, than lush garden plants. Most often a single flower or even a half-opened bud is put in a vase. Much attention is paid to the vase's correspondence to the selected flower, their proportional, textured, color harmony.

16 (See: Ueda Makoto. Literary and Art Theories in Japan, p. 73.)

The plot of the painting chosen for the tokonoma depended on the overall concept of the ceremony, and was associated with the season and time of day. There were also certain clichés of image associations. The picture with the winter scene was pleasant in the summer heat, on a cold winter evening a scroll depicting wild plum flowers was a harbinger of early spring.

Samples of painting, which were consonant with the ideals of cha-no-yu, appeared a few centuries before the ceremony, and tea masters had the opportunity to choose from the rich heritage of artists from China and Japan. These were most often paintings painted with mascara, which, in its abstraction from the color of real objects, was able to convey not only the appearance, but also the very essence of things. In this painting, it was not so much the plot that was important as the pictorial method itself and the associated technique of execution. 17

17 (See: Rawson Ph. The Methods of Zen Painting. - "The British Journal of Aesthetics", 1967, okt., Vol. 7, N4, p. 316.)

The poetics of reticence and hint in Zen painting intensified perception, as if drawing the viewer into the process of “finishing” the absent, completion of the unfinished. The asymmetrically located, shifted in one direction image was visually balanced by the unfilled background, which became the sphere of application of the emotional activity of the viewer and his intuition. The conciseness of the means was valued as an expression of the utmost compactness in the artistic organization of the pictorial plane, when one spot already forces one to perceive a white sheet of paper or silk as the infinite space of the world.

This general principle can be conditionally described as the “impact of absence”, when it is important not only what is directly perceived, but also what is not visible, but what is felt and affects no less strongly.

The characteristic features of Zen painting, its compositional features not only correspond to the general principles of the tea cult - they, in turn, help to clarify these principles, since it is in painting that the Zen attitude to the creative act and its result is embodied most fully and clearly.

Zen painting, like calligraphy, is by no means always cursive in style and expressive in emotional structure. The masterpieces of the famous Chinese artists My Qi and Liang Kai, which inspired Japanese masters, are in this sense very diverse. But maybe Sen no Rikyu. Flower vase at the tea ceremony. Bamboo. 1590 through the style of “flying” stroke and, as it were, accidentally fallen ink spots in calligraphic and pictorial cursive, it is easier to understand the tasks of the Zen picture, its unique features.

Among the surviving works of the great Sassu (1420-1506) there is a landscape in the “haboku style” (literally - broken mascara), which makes it possible to understand the very direction of the artist’s internal efforts and the closeness of these efforts to what the tea masters did. The task of Zen painting, as, however, in a broad sense - of all medieval art, was to find forms of transmission of what is beyond sensory perception - the invisible world of the spirit, contact with which was felt as contact with Truth, the Absolute, and in Zen Buddhism - as "insight".

According to the concept of Zen, this contact is a brief moment that transforms the whole inner essence of a person, his attitude to the world and self-perception, but may not at all affect the external course of his life, his daily activity. Thus, a brief moment of "illumination" remains, as it were, melted into the "massif" of eternity of being, its incessant gyres, the constancy of its variability. It would seem that the impossible task of combining the moment and eternity in the pictorial work, in essence, was the main one for the Zen artist, as well as for the master of tea.

"Landscape" (1495) Sassu is ideologically involved in "eternity", both in its motive (the infinite world of nature-cosmos, unchanged in its basic laws and embodying these laws), and in the canonicity of this motive and its method of realization (Sessu does not "invent "but following many generations of predecessors - Chinese and Japanese artists). However, the picture recorded a unique moment of ecstatic experience of the plot motive by the artist, resulting in an equally unique combination of strokes and mascara stains on a white sheet of paper field, transmitting not so much material forms - mountains, trees, nestling on a rock hut on the bank of the stream - but the image of a storm and raging rain, the beauty of which suddenly opened to the eyes in the elusive, changing and elusive outlines of objects. This impression did not arise as a result of gradual attentive scrutiny, but instantly and immediately, generated by a quick glance, so sharp that it penetrated the very essence of things, their true, hidden, and not only obvious meaning.

In the opening eye, fixed in the painter's handwriting and the stylistics of his letter to speed, “instantaneousness” of capturing subject forms, one can see a “imprint” of a soulful impulse, when the picture as if it is being born itself involuntarily arises and reveals in visible images the internal state of this short moment. ready to change in the next moment, go away, disappear 18.

18 (Wed the concept of intuitive knowledge in Zen Buddhism and the associated spontaneous “growth” from the inside to the outside, rather than creation (see: Watts A. The Way of Zen. New York, 1968).)

Changing the intensity of a tactile brushstroke, comparing a thick black or almost imperceptibly gray to the white background, imprinting the very pace of their imposition — the “abandoned” sharp oblique strokes of the brush, its light and soft touch to the surface of the paper — forms the complex duality of the temporal concept of landscape, just like the concepts of spatial (creation of several plans and infinite care in depth).

Theoretically, Zen Buddhism rejected the canonical church ritual and iconographic fixation of the object of worship. Outside of the mythological nature of Zen teaching, the requirement of inner work, not faith, to achieve satori meant an appeal to the ordinary and everyday, which at any moment can become the highest and sacred - everything depends on the person’s attitude to him, on his point of view. Truth, the “Buddha nature” could not be revealed to man through contact with the cult image, but through contemplation of a bird on a branch, bamboo shoots, or a mountain range in a fog. The identity of the ordinary and sacred implied the need for the life-likeness of forms reproduced by painting, their recognition at the level of everyday experience, which opened up the possibility of comprehending them at a higher level of spiritual essence. In Zen painting, a circle of subjects was gradually formed, which included, besides landscapes, images of animals, birds, Bodhisattva Kannon plants, Zen patriarchs, wise eccentrics Kanzan and Dzittoku. But the principled attitude to the visual motive was the same due to the basic tenets of the teaching, which called for comprehending its single essence and its integrity for the apparent plurality of forms of the world. Most importantly, there was no such direct connection between form and meaning as between form and the subject of the image 19.

19 (See: Rawson Ph. The Methods of Zen Painting, p. 337)

Such often noted closeness of Zen painting and calligraphy is determined not only by the unity of the means and the basic methods of writing, but first and foremost by the identity of the attitude to the hieroglyphic sign and the sign - the pictorial touch. Zen painting "remembers" the ancient, essential links with the hieroglyphic writing, its ideographic nature. The hieroglyph that embodies an abstract concept and at the same time carries in its forms the elements of visualization, became a model of Zen attitude to painting and its perception, the desire for such a unity of concept and image, the comprehension of which would be one-time, instantaneous movements from ignorance to knowledge). It was compared with satori, it was compared to him.

74. Dzaytyu-en tea house. Ceramics seto. Early 17th century Brocade cases for dzaytyu-an teapot

As a hieroglyph can have aesthetic qualities regardless of its meaning (when movement in the brush stroke is transmitted as such), a pictorial image can carry only a hint of a semantic concept, be almost only a spot, a stroke in which the outlines of specific objects are guessed. In such a stroke-spot something is recreated, only opened up to the artist, instantly flickering and disappearing, but capable of evoking an “echo”, “echo” in the soul of another person. Zen painting fundamentally denies the idea of completeness of the work, which would contradict both the notion of infinite and constant variability of the world, and the notion of mobility of perception, the appearance of a different meaning for the viewer depending on the specific moment, emotional mood and in general - his life and spiritual experience. So the Zen master tried to convey the invisible and not amenable to the image. Similar tasks, as already noted, set himself and the tea master, who tried in ritual, through all the senses and intuition to inspire his guests with something difficult perceptible, but extremely important, which constituted, in his opinion, the very essence of the world and man’s being.

Of the numerous diary entries about tea ceremonies preserved from the XVI-XVII centuries, with precise indication of the place and time of their conduct, the composition of the guests and the features of the utensils, it can be judged that every time serious internal work was required in preparing and conducting the action, so that the host and guests felt the result in themselves. As already noted, the ceremony was not nothing important, secondary. It is not surprising, therefore, that each piece of utensils was carefully selected mainly in terms of compliance with the general tone of ritual and harmony of the whole. Although already from the end of the 15th century, the basic rules of hell were defined, there was a rather active updating of the procedure, each master introduced all new and new elements into it. Like the whole ritual, the aesthetic properties of which were formed gradually from non-aesthetic, the utensils also initially had a completely different, practical meaning. Of the huge amount of utilitarian things, the masters of tea, choosing only those they needed, made up a new ensemble, with new tasks, where everything was re-realized in its functions and aesthetic properties.

75. Uji Bunrin Caddy and a bamboo spoon by master Gamo Udizato. XVI century. National Museum, Tokyo

At the very early stage of its addition, the Chinese utensils of the Song era were used mainly: blue-green bowls and vases of Longquan stoves, imitating the color of jade, milky-white and thick-brown glazes, which were called temoku in Japan, were used to imitate jade color.

Takeno Jo and his contemporaries found wide use of the products of Korean masters and their close Japanese ones. Along with refined bowls and vases with an inlaid pattern of colored clays, masters of tea began to use simpler ceramic utensils made for domestic use. In its artlessness, a special charm was first noticed.

But only with Saint-no Rikyu began the awareness of the value of aesthetic judgment and the own taste of each tea master. They were the first ceramic artists in the history of Japan, who, unlike artisans, began to make cups for their ceremonies themselves or directly direct potters. Masters of tea also cut out bamboo spoons, and Rikyu also made a bamboo vase. With his participation, he began to make cups of the famous ceramist Chojiro - the founder of the dynasty of masters of ceramics Raku.

The wide spread of tea ceremonies in the 16th century stimulated the development of many types of decorative arts and crafts. Ceramic and lacquered utensils made from time immemorial, iron kettles and various bamboo products have now become the subject of gathering, the demand for them has increased many times.

The expansion of the sphere of culture, the involvement of large segments of the population, awareness of the aesthetic value of the everyday things of the poorest population and thus their inclusion in the concept of beauty - all this constituted the most important stage in the formation of national aesthetic ideals in the 16th century based on a deep internal rethinking of foreign samples. A stormy flourishing of artistic crafts was connected with this - not only for the needs of the tea cult itself, but also for everyday life, the tea ceremony becoming an ideal model for it.

For example, the unprecedented scale was achieved by the production of iron pots (Kama), in which water boils during the ceremony. Among other tea utensils, a bowler is called a “master”. The most famous centers of this production were two - in Asia in the north of Kyushu and in Sano in eastern Japan (modern Tochigi prefecture). These centers have been known since the Kamakura era, and according to some sources, earlier 20.

20 (See: Fujioka Ryoichi. Tea Ceremony Utensils. New York, Tokyo 1973, p. 60)

In the numerous lacquer workshops of Kyoto, which experienced the rapid flourishing of their activities in the 16th century, mainly due to the execution of numerous items for the needs of the new ruling elite, artisans worked weeks and months, performing special little teapots (natsume) with a shiny black surface to order tea cult adherents decorated with paintings in gold or silver.

For the masters of tea, bamboo spoons of various "styles" were also made, and the names of their authors were preserved along with the names of famous ceramists and other artisans-artists: Sutoku, Sosey, Soin. Many tea masters themselves cut out spoons, which were subsequently especially appreciated. Bamboo made and whisks (tasas) for churning tea into foam. During the time of Murat Shuko, the first of the well-known authors of Tiasen, Takayama Sosetsu lived. It began a long dynasty of artisans, still existing in Kyoto.

But the tea cult had a particularly large, incomparable impact on the development of Japanese ceramics, which flourished from the middle of the 16th century.

As already noted, most of the items of tea utensils were made of ceramics. The first place, of course, belongs to the cup (tyavan) and the caddy (tau-ire), the next most important are the vessel for pure cold water (mizushashi), the vase for flowers (hana-ire), the vessel for used water (mizukoboshi or kensui). A small box for incense, a censer was also made of ceramics, and sometimes a stand for a lid removed from the pot (it also contains a bamboo ladle). In some ceremonies, guests are shown a large, egg-shaped vessel for tea leaves, usually standing in the utility room. Ceramics can be a stand for the brazier, used in the warm season; pottery was served when serving food (kaiseki) in some kinds of ceremonies.

It is clear that in the meaning and spirit of the ritual the cup was the central object among all the utensils. She was paid careful attention by both the host and ceremony guests. She owned the most dynamic role, she made the biggest movements and gave a lot of different impressions, besides just visual ones. It is not surprising that a great many cups of famous and unknown masters remained, highly valued and cherished as the most valuable national treasures.

Imported from China and highly prized in Japan bowls in the shape of an unfolded cone, covered with gray-blue or pure white glaze, sometimes with a network of small crackles crackles, caused the greatest number of imitations. Already at the end of the 15th century, Seto and Mino stoves in Central Japan produced a large number of cups covered with pale yellow glaze (yellow seto type) and various shades of brown glaze, thick drops flowing down to the ring leg, which remained unglazed. Irregularities and stains in the glaze, crackle, the contrast of the shiny glazed surface and the matte clay base, finally, the soft, rounded silhouettes of the cups formed the basis of their expressiveness and charm. In the second half of the 16th century, under the influence of the aesthetic program of the tea cult, these same furnaces began to produce cups of a more closed, cylindrical shape with a thick, slightly uneven edge, irregularly applied porous glaze, and sometimes with a wide, sweeping pattern (products like sino and oribe).

Ceramic centers on the islands of Kyushu, many of which were founded by Korean masters in the XIV century, as well as masters, forcibly transported here during the conquests of Hideyoshi in 1592 and 1597, originally in their forms and style of painting were very different from those produced in the central provinces , and only the increased demand for tea utensils influenced some of their change. The largest ceramic center was Karatsu in Hizen province, in northwestern Kyushu, as well as Takatori and Agano, in northeastern Kyushu, Satsuma, in the south, Yatsushiro, in the central part of the island, and Hagi, on the southernmost tip of Honshu. Products of all these stoves were rather heavy, with a thick crock, exquisitely coarse in the imposition of glaze and painted decor, which was greatly appreciated by many tea masters. The same qualities, but in even more explicit terms, were characteristic of the production of stoves that have long worked for local peasant needs, in Bizen, Shigaraki and Tamba, considered the oldest stoves in central Japan. Cups, jugs, cylindrical vessels produced by furnaces were simple and unassuming. They were made of local porous clay of reddish and reddish-brown shades; their only decor was ash-caked and irregular dark spots that appear during firing as a result of different traction and temperature in the kiln. It is this irregularity, the rough roughness of the products, their rustic simplicity and attracted the masters of tea. Especially often products Tamba, Sigaraki and Bizen were used in tea ceremonies as vessels for water and flower vases. Their properties, as if re-discovered and noticed by the masters of tea in a variety of products by unknown masters, were recreated and brought to great acuteness and underlined expressiveness in the works of ceramics artists who produced products for cancer. The representative of the fourteenth generation of these masters and now works in Kyoto.

![]()

In ceramics to raku, those qualities which were generalized by tea masters in the term wabi, were most fully embodied. The impersonality of the peasant utensils with all its features was connected here with the artistry of the individual plan, expressing the uniqueness of the work of art. The first in the line of masters of raku was Tanaka Chojiro (1516-1592), who began his work with the manufacture of tiles, and after meeting with San No Rikyu under his leadership, he made cups for the tea ceremony. The name of the cancer began to be put on the products of the furnace, starting with the works of the representative of the second generation of Jokai masters, who received a gold seal with the hieroglyph "cancer" (pleasure) from Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The renowned master was a representative of the third generation of masters of raku - Donu, also known as Nonko.